As a follow up to my post about New American Industrialism and the Importance of Company Culture, I’m sharing some thoughts here on how we inspire, recruit, retain, and embrace the trades as a critical piece of reindustrializing America.

Said simply: we cannot reindustrialize America without tens or hundreds of thousands of additional people joining the trades across all industries - electricians, plumbers, aerospace technicians, PLC programmers, factory associates, and everything in between. Much fanfare goes into the technologies driving the industrial revolution in America, but much less attention is paid to those who will actually be using those technologies to build the products and services of our future.

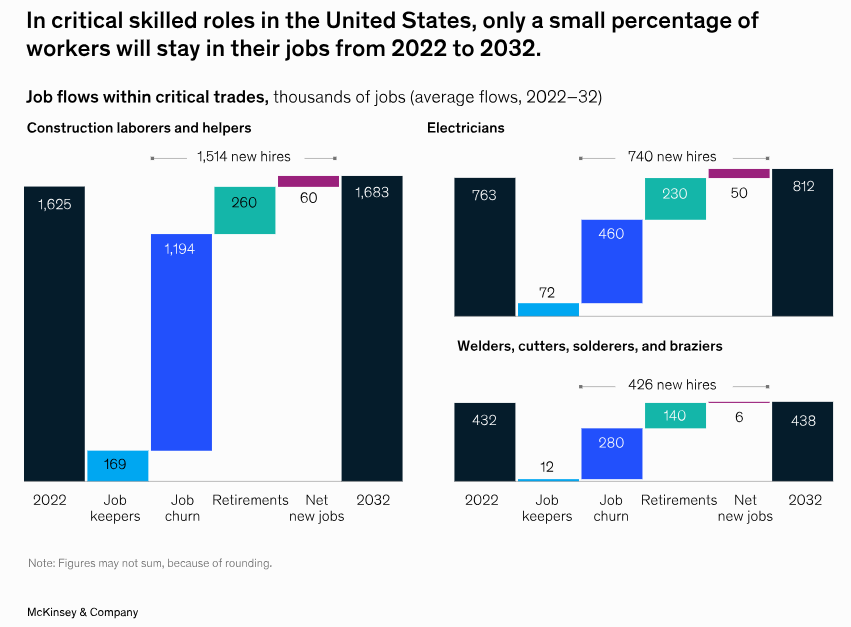

Don’t take it from me: this excellent McKinsey article on the subject double underlines the deep need for workers in the trades.

Inspiring and Recruiting

The first step in rebuilding America’s industrial base has to be the cultural change of making it cool to pursue a career in the trades again. For the last quarter of the last century and the first quarter of this one, America has steadily lost a significant number of people in manufacturing, all while the US population has nearly doubled.

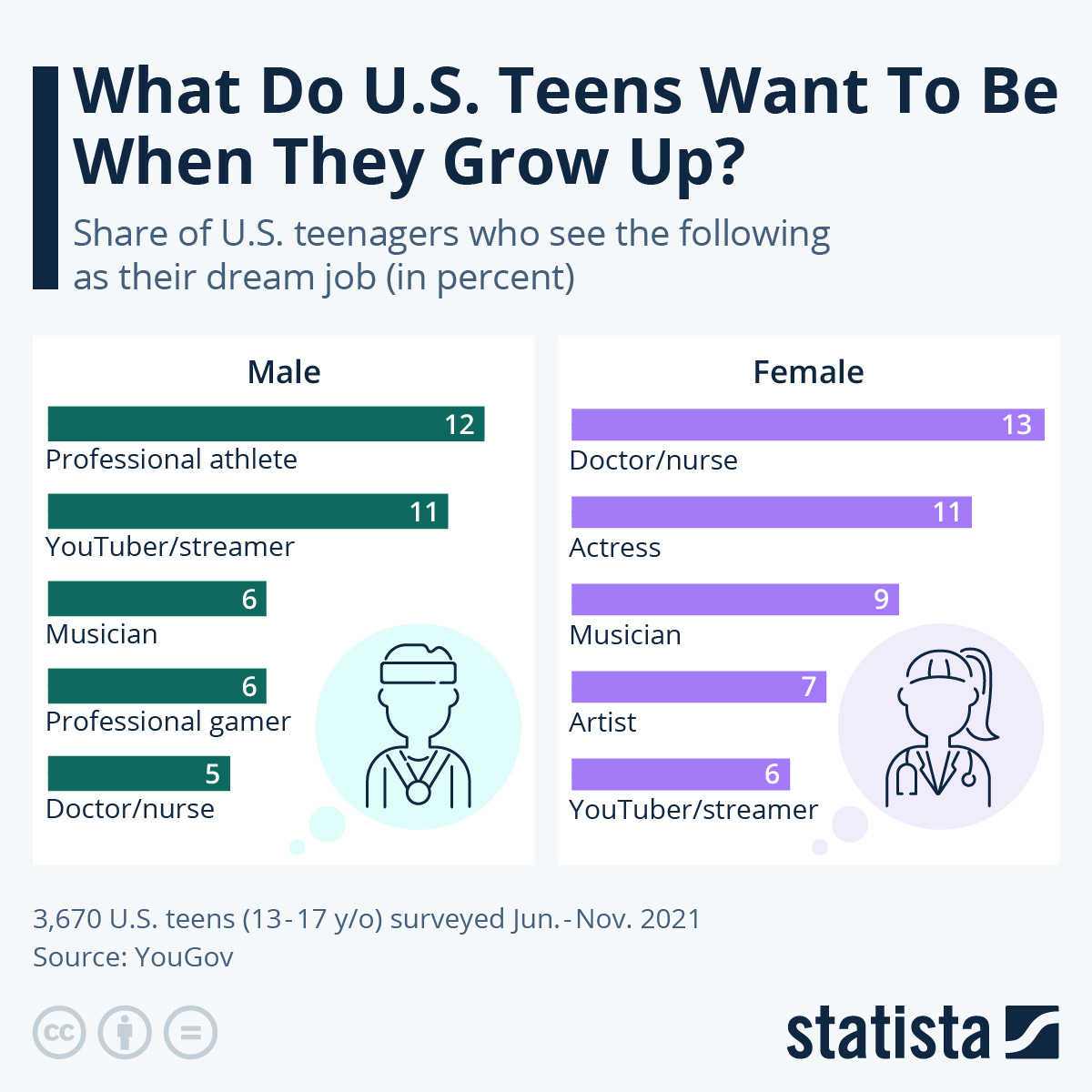

Today, high schoolers are oftentimes not even aware that manufacturing or trades work is available to them. ‘Professional’ jobs such as doctors, lawyers, finance professionals and engineers are held in high regard, all of which typically involve a 4+ year education. These ‘prestigious’ job categories by default result in trades work being viewed in a second class way, creating a gap in perceived status of these jobs. The college for all movement from the early 2000’s accentuated this trend. So, how do we reverse this trend?

Pop Culture about the Trades

Especially in today’s media-saturated environment, there needs to be some content that shows the trades in a positive light. There have been examples of video-based format shows that highlight this type of work, albeit in different capacities. Two that stick out amongst many are Mike Rowe’s Dirty Jobs and the Canadian show How It’s Made. Below, I break down the relevant pieces of both.

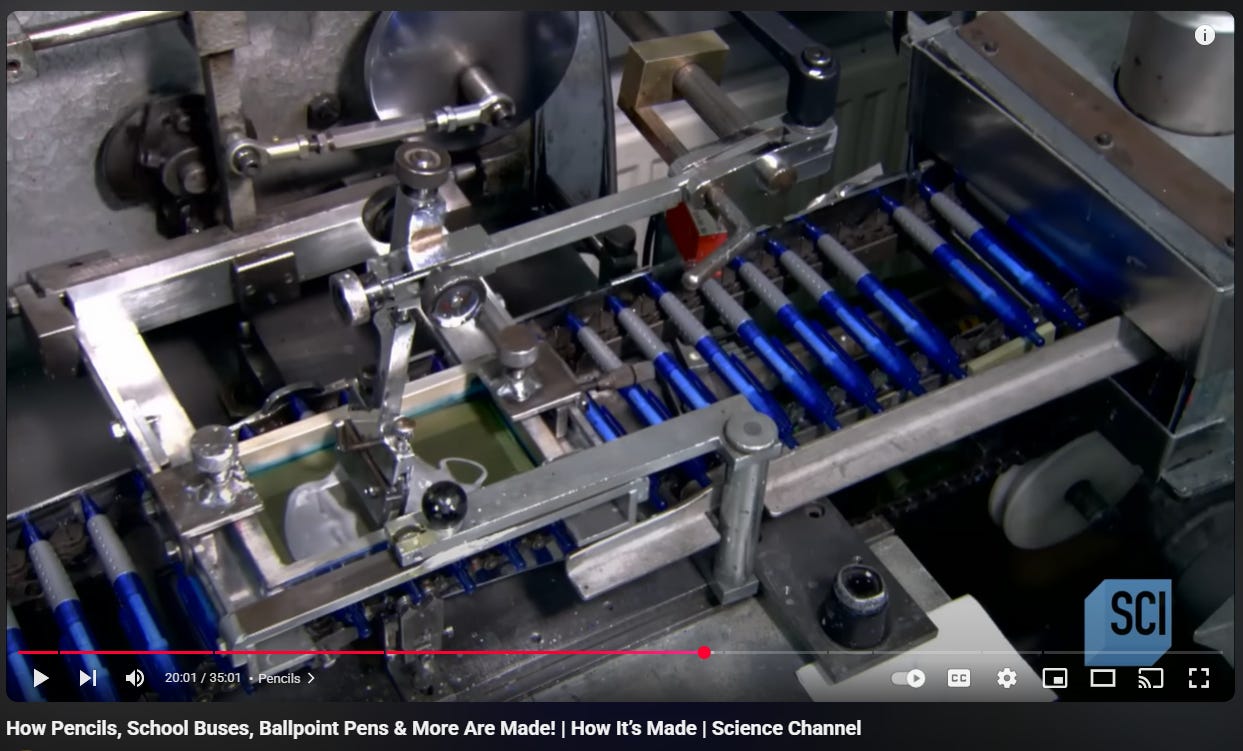

How Its Made

How It’s Made was a very long-running show, from 2001 to 2019, over 416 episodes covering over 1000 products. This show was really focused on the manufacturing process, with the primary medium including voiceover describing a process that was being filmed without audio included. The show was ‘hosted’ only via audio, and they made a fairly large effort to avoid showing people, or adding personality to the show. In this way, it was ‘pure’ manufacturing: focused on the process, tools, and machines, and not people. Furthermore, often basic and common household items were featured, increasing interest amongst the uninitiated to manufacturing. The success of How It’s Made should not go unnoticed; and it remained largely the same format in the 18 years it was airing.

How It’s Made is a solid example, and is a show that I grew up watching, nearly religiously, for nearly two decades. That said, I can offer a few critiques:

The show was highly dehumanized. They went to great lengths to avoid showing the humans behind the processes and products. Interviews with or clips of the people working on the line would not only make it more enjoyable to watch, but would relay the cool factor of the job, not just the nuts and bolts of the job.

It wasn’t visually hosted. A host walking through the assembly line pointing to various equipment would increase humanity similarly.

The interconnectedness of the process was underdeveloped. Oftentimes, an episode would start with a zoomed-in shot of a machine making a repetitive motion. It was unclear how this step played in to the larger process of manufacturing the item. Instead, an overview or graphic showing “where you are in the process” would help viewers understand the larger picture. Also, show the product in use. These are bedrock products in big markets touching in some cases billions of people.

Dirty Jobs

The most relevant example is Dirty Jobs, perhaps the most successful show in this genre ever produced. Over 10 seasons and 179 episodes, Dirty Jobs did more to highlight roles in manufacturing, construction, farming, energy, and several other sectors than any other show in history. Built around a wide audience, Mike made the show fun, interesting, funny, and at times thrilling for the casual viewer. Grandmas, kids, blue collar, white collar, and everyone in between at some point saw Mike on Dirty Jobs, highlighting the individuals who “do the jobs others don’t want.” Mike built up the people he worked alongside as heroes, while simultaneously educating the viewer on the “what”, “why”, and principally “how” of the work at hand. He playfully was able to make fun of the jobs and people he worked alongside on the show without disparaging them.

Dirty Jobs somewhat rarely focused on traditional manufacturing, but instead focused on other ‘blue collar’ work areas like farming, waste services, construction, food processing, and construction.

I find it hard to find fault with Dirty Jobs as it relates to this mission - it was essentially spot on. However, I can offer some differences with the contemplated videos or show in this document:

Dirty Jobs focused on jobs that were, well, dirty. I’d argue that being less focused on this specific trait, and instead more uplifting about how rewarding the jobs are, the better.

If Dirty Jobs was 75% human and 25% job, I’d bias a little more towards the job, and the surrounding tools and processes.

Subjects typically were jobs that supported human lifestyle, rather than made new technology. In fact, many jobs highlighted showed conventional rather than modern processes. For this new idea, I would think that showing the modern technology behind many of these jobs would aid in inspiring folks - many of which use and are fascinated by modern technology - to join the fields.

A new set of content like How Its Made and Dirty Jobs would be able to visually show high schoolers what the trades are, elevate their importance, and educate them on the cool careers available to them in these fields.

Retaining

Once we have more people inspired to join companies in the trades, how do we ensure that folks stay in these jobs long term?

In several trades, licensing levels ensure that there is a clearly defined career path. This is something that should be in every trade, and companies should strive to provide growth opportunities for folks as a method of retention. For example, in the electrical trade, 4 levels from apprentice to master electrician are available, and give folks something to look forward to. In larger organizations, paths into mentorship and leadership also help retain folks for their careers via offering a viable pathway to a high salary, good lifestyle, and differentiated skillset.

The trades often are characterized by high labor churn, further exacerbating the staffing challenge that many companies face.

Embracing

By ‘embracing’, I mostly mean in the cultural sense. In my trips to China, this is a key difference I’ve noticed compared to the US. In China, manufacturing jobs are highly coveted, particularly as a means for poor rural folks to obtain a decent living in an urban environment. As such, many young people strive to land a job in a manufacturing or construction trade, and while they’re there, they often enjoy organizational clout on par with engineers or other roles that require a college education. While that is hard to replicate here, what we can do is elevate manufacturing and the trades within organizations.

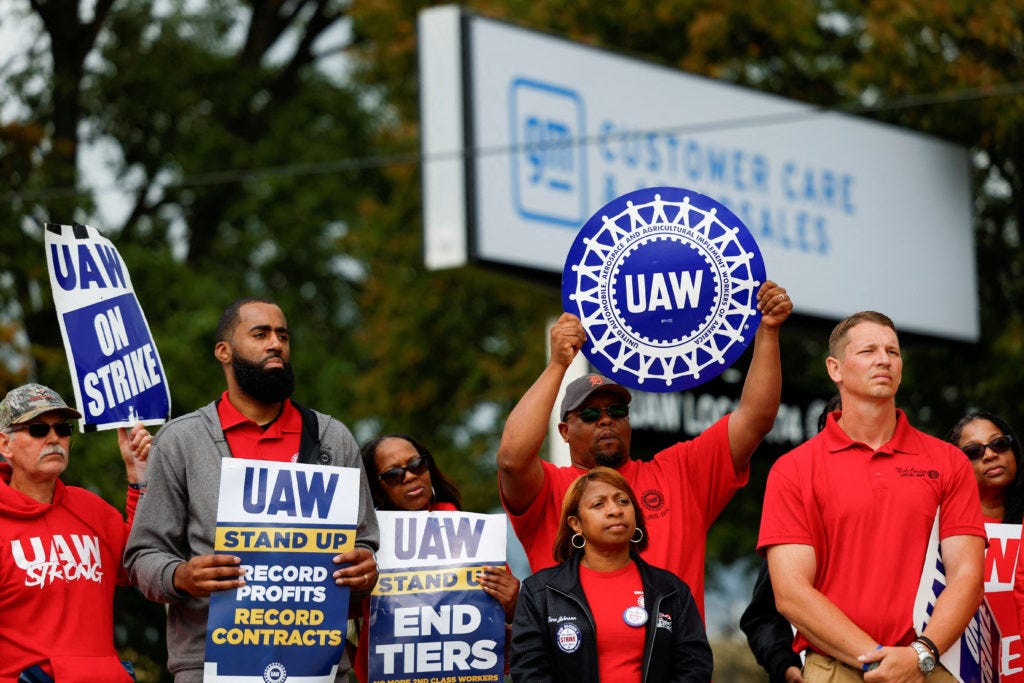

Unions

In particular, I’ve found many companies to have an us vs. them mentality between labor (aka the trades) and management. This is most evident in highly unionized industries such as automotive, where being a part of one group and not the other is a badge of honor - just walk around Detroit for a day and you’ll see tons of United Auto Workers gear on people. Maybe counterintuitively, I believe that deemphasizing unions will lead to more people in the trades, not less. By deemphasizing unions (such as having new entrants like Rivian and Tesla), more the us vs. them mentality is reduced, costs to be in the trades are reduced (union dues are expensive), and ultimately companies will be able to hire more employees as they expand factories as opposed to offshoring them.

I admit I wanted to be the Dallas Cowboys quarterback growing up.